Vertigo after head injury: Post-traumatic BPPV

Vertigo can occur after head injury, concussion/mTBI, and other traumatic brain injuries - it is most often caused by Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). Learn more about post-traumatic BPPV and how vestibular rehab can help.

What is BPPV?

BPPV is an inner ear disorder that causes episodes of vertigo lasting less than a minute. These episodes are triggered by movements like lying down, turning in bed, bending down, and looking up. It is the most common cause of vertigo in adults, and the most common vestibular disorder across the lifespan. As well as causing vertigo, BPPV can lead to imbalance, increase your risk of falling, and affect your ability to perform everyday activities. The good news is that BPPV can be very safely and effectively treated, and there is strong research evidence and clinical practice guidelines to guide best care.

The name of this condition describes what happens:

Benign = not due to a serious disorder & favourable prognosis

Paroxysmal = sudden & brief recurrences

Positional = occurs with head position change relative to gravity

Vertigo = illusion of motion of yourself or your surroundings (often spinning)

We have calcium carbonate crystals (known as otoconia) that are normally embedded in part of our inner ear called the utricle. In BPPV, these crystals become dislodged and move into the semicircular canal(s). As we move our head and change positions, the dislodged crystals move with gravity, causing fluid in the semicircular canal to move when it would normally be still. This sends false, mismatched signals and produces nystagmus (abnormal involuntary eye movements) and vertigo.

Unfortunately, BPPV is often underrecognized and not appropriately evaluated or treated. About 86% of individuals with BPPV seek medical consultation, are not able to perform their usual daily activities, or lose time at work, but only 8% receive effective treatment.

Symptoms of BPPV

Spells of vertigo (but not always spinning or rotation)

Vertigo lasts less than 60 seconds

Triggered by changes in head position relative to gravity like lying down, turning in bed, bending forward, and looking up

BPPV is often associated with nausea, vomiting, imbalance, motion sensitivity, and anxiety

How common is BPPV?

Research indicates that 2.4% of people will experience BPPV in their lifetime, and 1.6% will have BPPV each year. BPPV is more common as we get older, and about 3.4% of people over 60 years of age will experience BPPV every year.

Risk factors for BPPV

More common with older age, peak incidence at age 50-80 years

More common in women

More common with other inner ear disorders (like Meniere’s Disease, vestibular migraine, and after vestibular neuritis)

More common in people with migraine

High blood pressure and high cholesterol are risk factors

Vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor

Osteoporosis/osteopenia is a risk factor for BPPV and for BPPV recurrence

BPPV is common after head injury

What is post-traumatic BPPV?

In people under the age of 50, the most common cause of BPPV is head injury. BPPV is unfortunately quite common after head and neck trauma. Direct trauma to the head or indirect whiplash-type forces can cause otoconia to become dislodged. Post-traumatic BPPV can occur even without a direct blow to the head, for example the deceleration force of falling can cause crystals to come loose. Post-traumatic BPPV usually occurs in the first two weeks after the trauma.

In a study completed at UHN Toronto General Hospital, 23% of adults with work related head injury had a suggestive history or diagnosed BPPV. In another study of adults with head trauma evaluated in the emergency and neurosurgery departments at Oslo University Hospital, 21% developed BPPV within 3 months of their injury.

Children and teens can also be affected by BPPV after a head injury. In a study of pediatric and adolescent patients with dizziness post-concussion, 29.4% were diagnosed with BPPV. Another study of pediatric patients with dizziness found BPPV in 19.8%, and the most common comorbidity in these patients with BPPV was concussion.

Compared to idiopathic BPPV (meaning the type that happens spontaneously and not due to head injury), post-traumatic BPPV is more likely to:

Reoccur

Require multiple treatments

Occur in both ears

Occur in multiple canals

BPPV has a relatively high recurrence rate. It has been estimated that approximately 50% of people with BPPV experience at least one additional episode within two years. The recurrence rate of post-traumatic BPPV tends to be higher than idiopathic BPPV. This may especially be the case if the head injury also caused otolithic dysfunction or injury to the utricle.

Treatment of post-traumatic BPPV

BPPV can go away on its own without treatment - it resolves spontaneously in about 20% of people by one month and in about 50% of people by three months. But while it is active, the symptoms can be very distressing and disabling! Treatment is very effective and can improve your symptoms much faster than waiting.

BPPV can be very effectively treated with canalith repositioning maneuvers. These are special exercises that move your head and body into specific positions, to move the loose crystals around the semicircular canal and back out into the utricle.

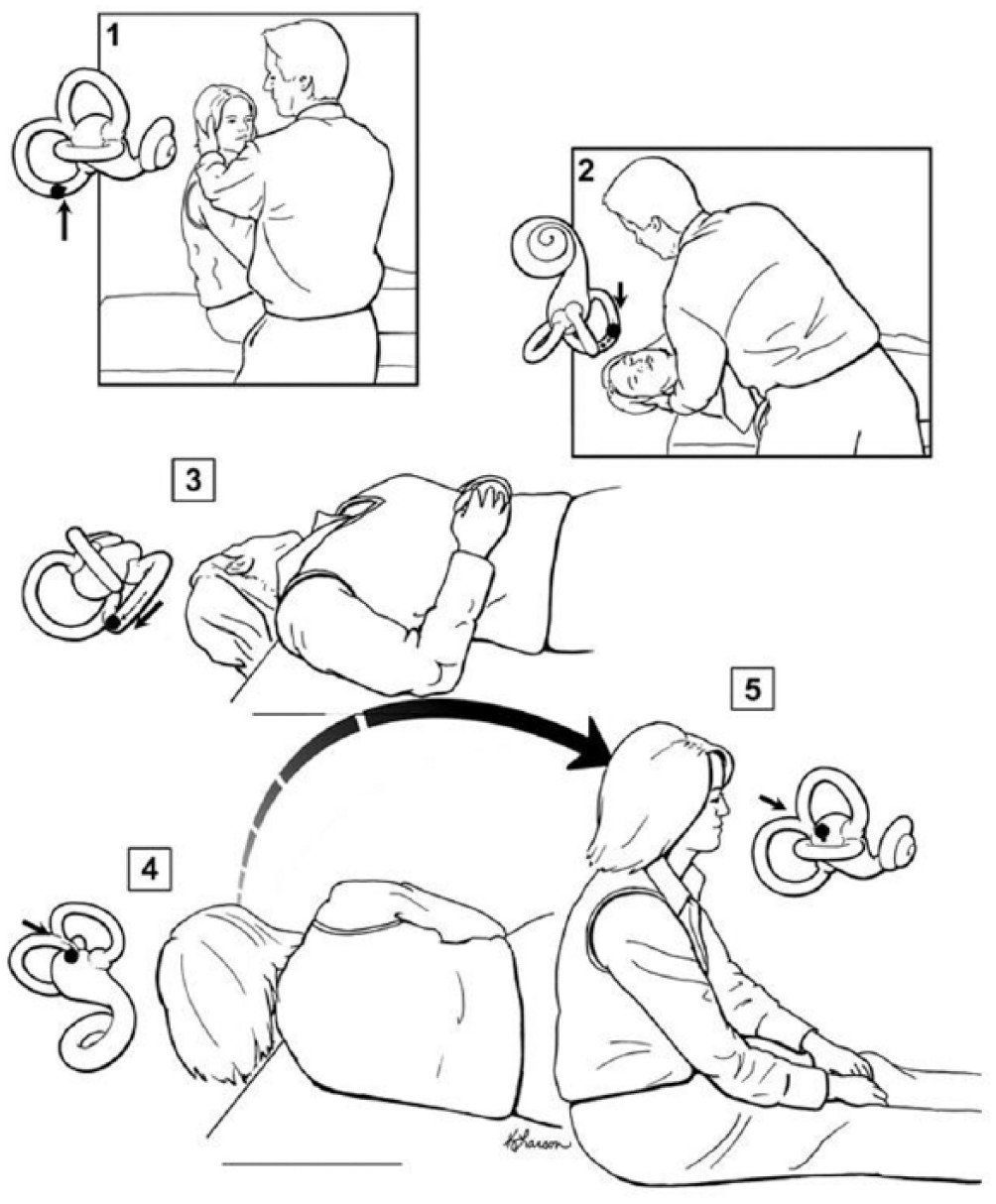

Epley maneuver from Bhattacharyya et al 2017

An evaluation usually starts with an interview to understand your symptoms and medical history, and a complete assessment involves ruling out other causes of vertigo. To determine if you have BPPV, we use the Dix-Hallpike test and observe for nystagmus to determine what ear and which canal is affected. Treatment maneuvers are specific to the involved ear and canal. The posterior canal is most commonly affected, and this is typically treated with Epley or Semont maneuvers. The horizontal canal is the next most commonly involved, and this is typically treated with Lempert/BBQ roll or Gufoni maneuvers. Sometimes it can be challenging to determine what part of the ear is involved, particularly when there are multiple canals affected as this can cause an atypical pattern of nystagmus. This is why seeing an experienced vestibular rehabilitation physiotherapist can be beneficial.

Post-traumatic BPPV can be harder to treat and require more treatment sessions than the idiopathic form. Research demonstrates that for 80 to 90% of individuals, BPPV resolves completely after 1 to 2 treatments. For some people it can take several treatment maneuvers across several treatment sessions to get rid of symptoms. This is especially the case if BPPV is due to head trauma, or if it affects both ears or multiple canals.

Even if we initially resolve your BPPV with treatment, it can reoccur. It is important to work with your physiotherapist to come up with a plan for what to do if your symptoms return. For some people this is as simple as booking a follow up visit. Other people prefer to have exercises or maneuvers to try at home first and know when to seek follow up with their vestibular rehab therapist or ENT. Research suggests that one in five recurrences happen in a different semi-circular canal, so if self-treatment is not helping it could be because you need to treat a different part of the ear with a different maneuver.

In some cases, BPPV can be very persistent or recurrent. If it keeps coming back, limits your daily activities, and does not respond to conservative treatment with physical therapy and repositioning maneuvers, you may benefit from referral to an ENT/otolaryngologist or neurotologist to consider whether you are a candidate for semicircular canal occlusion surgery. This surgery blocks the canal affected by BPPV (usually the posterior canal), so any loose crystals can no longer move into the canal. You may require additional vestibular rehab after this type of surgery - our physiotherapists at Vestibular Health have experience consulting with ENT surgeons, and working with individuals before and after canal occlusion surgery.

If you have post-traumatic BPPV, it can be helpful to find a vestibular rehab physiotherapist very experienced working with complex cases of BPPV. It is also helpful to find a provider who performs assessments using infrared video goggles to allow more sensitive and complete assessment and to help guide treatment maneuvers. This is particularly important if you have more than one ear or canal involved, or if you have already tried self-treatment maneuvers on your own but still have symptoms.

Some people experience residual imbalance and motion sensitivity after having BPPV, and vestibular rehabilitation exercises can help you recover. It is very common to have other vestibular symptoms after head injury or concussion like dizziness, balance problems, and visual motion sensitivity. Vestibular rehab can help with these issues too!

If you are struggling with positional vertigo, get in touch to book an appointment with one of our physiotherapists.

Thumbnail image source: Kao, Parnes, & Chole 2016

-

Bhattacharyya, N., Gubbels, S. P., Schwartz, S. R., Edlow, J. A., El-Kashlan, H., Fife, T., Holmberg, J. M., Mahoney, K., Hollingsworth, D. B., Roberts, R., Seidman, M. D., Steiner, R. W. P., Do, B. T., Voelker, C. C. J., Waguespack, R. W., & Corrigan, M. D. (2017). Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 156(3_suppl), S1–S47. [link]

Andersson, H., Jablonski, G. E., Nordahl, S. H. G., Nordfalk, K., Helseth, E., Martens, C., Røysland, K., & Goplen, F. K. (2022). The Risk of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo After Head Trauma. The Laryngoscope, 132(2), 443–448. [link]

Carr, S., & Rutka, J. (2017). Post-Traumatic Dizziness. Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports, 5(2), 142–151. [link]

Chen, J., Zhao, W., Yue, X., & Zhang, P. (2020). Risk Factors for the Occurrence of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 506. [link]

Gordon, C. R., Levite, R., Joffe, V., & Gadoth, N. (2004). Is Posttraumatic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo Different From the Idiopathic Form? Archives of Neurology, 61(10), 1590. [link]

Kim, J.-S., & Zee, D. S. (2014). Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(12), 1138–1147. [link]

Brodsky, J. R., Lipson, S., Wilber, J., & Zhou, G. (2018). Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) in Children and Adolescents: Clinical Features and Response to Therapy in 110 Pediatric Patients. Otology & Neurotology, 39(3), 344–350. [link]

Wang, A., Zhou, G., Kawai, K., O’Brien, M., Shearer, A. E., & Brodsky, J. R. (2021). Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo in Children and Adolescents With Concussion. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 13(4), 380–386. [link]

von Brevern, M., Radtke, A., Lezius, F., Feldmann, M., Ziese, T., Lempert, T., & Neuhauser, H. (2006). Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: A population based study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 78(7), 710–715. [link]

Evans, A., Frost, K., Wood, E., & Herdman, D. (2024). Management of recurrent benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 138(S2), S18–S21. [link]