Persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD)

What is PPPD?

Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness causes chronic symptoms of dizziness, non-rotatory vertigo, and/or imbalance. The short form is PPPD - pronounced “three-P-D” or “triple-P-D” (it is also sometimes written as 3PD).

PPPD is a newer term, but features of this diagnosis have been previously described using other terms such as space-motion discomfort, visual vertigo, phobic postural vertigo, and chronic subjective dizziness.

PPPD usually develops after a triggering event that was associated with vertigo, dizziness, or imbalance. This initial acute event then leads to the chronic symptoms of PPPD.

What are the symptoms of PPPD?

The main symptoms of PPPD are dizziness, unsteadiness, and non-spinning vertigo.

Dizziness > a non-motion sensation that is often described as cloudiness, fogginess, fullness, heaviness, or lightness in your head, or a feeling of spatial disorientation

Unsteadiness > a feeling of being unstable, off balance, or wobbly, or a feeling of veering when walking

Non-spinning vertigo > a feeling of movement like swaying, rocking, bouncing, or bobbing, which can be felt internally (inside your own head or body) or externally (your environment moving)

What causes PPPD?

PPPD often starts after a triggering event that causes acute vertigo, dizziness, or imbalance. Examples of triggering events include vestibular neuritis, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), vestibular migraine, panic attacks, concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), or dysautonomia (like POTS).

Although the initial acute vestibular symptoms improve, you are left with chronic symptoms that are often different in quality from the initial event. For example, you may have experienced spinning vertigo and severe imbalance lasting hours due to vestibular neuritis. After the initial event the spinning went away and your balance improved, but then you started to feel a sensation of rocking when you are standing up and started to feel dizzy in busy environments.

People with pre-existing anxiety or who experience high anxiety during their acute vestibular episode may be more predisposed to developing PPPD. In addition, there is often an interrelationship between anxiety and the chronic vestibular symptoms experienced with PPPD. Having symptoms can be anxiety provoking, and anxiety can increase how sensitive you are to symptoms.

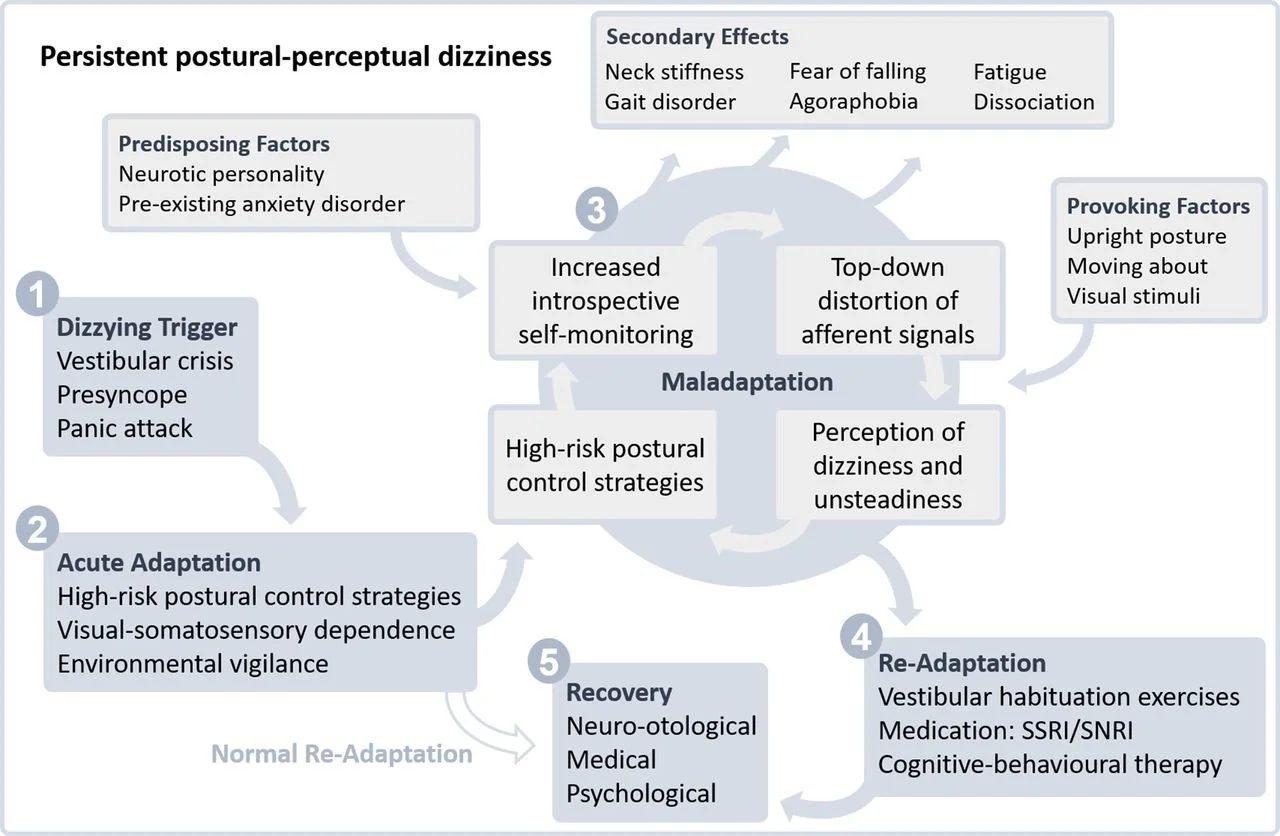

When your balance is disrupted or you have a sudden experience of vertigo or dizziness, your brain can make changes to how you interpret different sensations and to how you move your body, in order to keep you safe. This change is initially a helpful and protective process, but with PPPD this change persists beyond the timeframe where it would be helpful, so it becomes maladaptive. For example, if your vestibular system is sending abnormal signals or if you are in a situation that is high risk to your balance, your brain adapts to protect you by relying more on visual inputs, paying more attention to your movements, and paying more attention to your environment. Your brain also changes your movement patterns in situations where you are at high risk of falling with potentially dangerous consequences, for example your body gets stiffer and your steps become shorter. As the initial dizziness or vertigo episode resolves and the potential risk decreases, your nervous system should reset back to a normal state. In PPPD, your brain stays stuck in “high alert” mode, and remains over-protective and hypersensitive.

In this “high alert” state, you can become hypersensitive to normal head movements and normal body sway. This can cause increased worry about falling and cause you to pay more attention to keeping your balance, such that your movement becomes less automatic.

This change in processing of sensory information often involves over-relying on visual inputs, and under-using vestibular and somatosensory information. Relying too much on visual information can increase how sensitive you are to seeing things move in your environment, busy patterns or complex visual stimuli, or situations of optic flow (meaning visual motion that results from you moving through your environment, like walking down a grocery store aisle). These types of symptoms are often called visual motion sensitivity.

Avoidance of movements or environments that provoke symptoms can actually worsen hypersensitivity over time, and can increasingly limit your day-to-day function.

Figure showing the cycle of maladaptation that occurs in PPPD (from Popkirov et al 2018)

Risk factors for PPPD

Research has shown there are several factors that appear to be related to developing PPPD. These factors appear to predispose people to go on to develop chronic dizziness after an initial triggering event:

High anxiety at the time of and early after the triggering event

High body vigilance - increased attention to and awareness of body sensations

Catastrophic thinking - a high degree of worry about causes and consequences of symptoms

Autonomic arousal - the physical stress response associated with anxiety which can include increased heart rate, increased breathing rate, sweating, shaking, upset stomach, dry mouth

Visual dependence - over reliance on vision for balance

The severity of the initial acute event and the severity of vestibular loss do not appear to predict development of PPPD.

How is PPPD diagnosed?

The Bárány Society has outlined specific diagnostic criteria for Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness. PPPD is defined as a chronic vestibular disorder and all five of the criteria below need to be present to make the diagnosis.

A. One or more symptoms of dizziness, unsteadiness, or non-spinning vertigo are present on most days for 3 months or more.

Symptoms last for prolonged (hours-long) periods of time, but may wax and wane in severity.

Symptoms need not be present continuously throughout the entire day.

B. Persistent symptoms occur without specific provocation, but are exacerbated by three factors:

Upright posture,

Active or passive motion without regard to direction or position, and

Exposure to moving visual stimuli or complex visual patterns.

C. The disorder is precipitated by conditions that cause vertigo, unsteadiness, dizziness, or problems with balance including acute, episodic, or chronic vestibular syndromes, other neurologic or medical illnesses, or psychological distress.

When the precipitant is an acute or episodic condition, symptoms settle into the pattern of criterion A as the precipitant resolves, but they may occur intermittently at first, and then consolidate into a persistent course.

When the precipitant is a chronic syndrome, symptoms may develop slowly at first and worsen gradually.

D. Symptoms cause significant distress or functional impairment.

E. Symptoms are not better accounted for by another disease or disorder.

PPPD can co-exist with other vestibular or neurological disorders. This means you can have another vestibular diagnosis and also have PPPD. For example, vestibular migraine can be a trigger or perpetuating factor in PPPD.

If you have PPPD, your test results may be completely normal. In general, vestibular function testing looks at the function of your “hardware” and PPPD is a “software” problem.

How common is PPPD?

PPPD is a very common cause of chronic symptoms. PPPD is diagnosed in 14% of people seen by primary care and 20% of people seen by neurology for vestibular or balance problems. More than 50% of people seen in multidisciplinary dizziness clinics have PPPD either as the only diagnosis (in about 9%) or in addition to other conditions (in about 44%). PPPD seems to be more common in women.

PPPD treatment

Current research evidence supports treating PPPD using medications, counseling, and physical therapy. These treatments are often used in combination to achieve the best results.

Medication > selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) can reduce symptoms of PPPD

Counseling or psychotherapy > cognitive-behavioural therapy can improve dizziness and anxiety in PPPD

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy > exercises and strategies to improve vestibular symptoms and physical function

Vestibular rehab for PPPD

A physiotherapist with training in vestibular rehabilitation and experience working with people with PPPD can provide you with a custom treatment program, and will work with your other health care providers to help you understand and improve your symptoms. Physical therapy for PPPD is individualized to your particular challenges and goals but can include:

Balance exercises > exercises to improve your balance focused on 1) up-training the use of vestibular and proprioceptive inputs and down-regulating the use of visual inputs; and 2) normalizing hypersensitivity to body sway and normalizing balance reactions

Habituation exercises > targeted exercises to gradually decrease sensitivity to provoking movements

Symptom de-escalation > strategies to manage and cope with symptoms when they do occur

Functional goal setting > strategies to gradually resume the activities that are most meaningful and important to you

PPPD can co-occur with other vestibular disorders, so physiotherapy interventions may also target other problems for example with gaze stability or VOR adaptation exercises , or BPPV treatment maneuvers.

Want more information or to see if vestibular rehab could help you? Call us to talk to one of our physiotherapists.

-

Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. Journal of Vestibular Research. 2017;27(4):191-208. [link]

Staab JP. Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Neurologic Clinics. 2023;41(4):647-664. [link]

Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(1):5-13. [link]

Powell G, Derry-Sumner H, Rajenderkumar D, Rushton SK, Sumner P. Persistent postural perceptual dizziness is on a spectrum in the general population. Neurology. 2020;94(18):e1929-e1938. [link]

Popkirov S, Stone J, Holle-Lee D. Treatment of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) and Related Disorders. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20(12):50. [link]

Waterston J, Chen L, Mahony K, Gencarelli J, Stuart G. Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness: Precipitating Conditions, Co-morbidities and Treatment With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:795516. [link]

Staab JP. Behavioral aspects of vestibular rehabilitation. Hoffer ME, Balaban CD, eds. NRE. 2011;29(2):179-183. [link]

Thompson KJ, Goetting JC, Staab JP, Shepard NT. Retrospective review and telephone follow-up to evaluate a physical therapy protocol for treating persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: A pilot study. Journal of Vestibular Research. 2015;25(2):97-104. [link]

Yu YC, Xue H, Zhang Y xin, Zhou J. Cognitive Behavior Therapy as Augmentation for Sertraline in Treating Patients with Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:1-6. [link]

Nada EH, Ibraheem OA, Hassaan MR. Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy Outcomes in Patients With Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2019;128(4):323-329. [link]

Zang J, Zheng M, Chu H, Yang X. Additional cognitive behavior therapy for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: a meta-analysis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;90(3):101393. [link]

Herdman D, Norton S, Murdin L, Frost K, Pavlou M, Moss-Morris R. The INVEST trial: a randomised feasibility trial of psychologically informed vestibular rehabilitation versus current gold standard physiotherapy for people with Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness. J Neurol. 2022;269(9):4753-4763. [link]

Trinidade A, Cabreira V, Goebel JA, Staab JP, Kaski D, Stone J. Predictors of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) and similar forms of chronic dizziness precipitated by peripheral vestibular disorders: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94(11):904-915. [link]